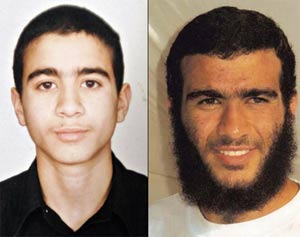

Boy soldier Omar Khadr pleads guilty before Guantanamo Military Commission ... Plea deal saves the US the embarrassment of conducting the "trial" of a boy soldier ... Stephen Keim and Katherine McGree report  Omar Khadr: man and boyAs expected, Omar Khadr, an alleged child solider charged with conspiracy, murder, aiding the enemy and providing material support to Al Qaeda has pleaded guilty to all five charges against him.

Omar Khadr: man and boyAs expected, Omar Khadr, an alleged child solider charged with conspiracy, murder, aiding the enemy and providing material support to Al Qaeda has pleaded guilty to all five charges against him.

Under the terms of the plea deal he will serve up to eight more years in prison - in addition to the eight he has already spent in detention.

There is an agreement that the United States will support Khadr's eventual application for a transfer to Canada.

During his sentencing hearing Khadr apologised to the widow of the US soldier it is agreed he killed.

Khadr's trial was to have been the first before a Guantanamo Military Commission under the Obama administration. He is now the fifth person at Guantanamo to be convicted of war crimes.

Here is the stipulations of fact in his case put forward by the prosecution.

At age 15 Khadr, a Canadian citizen, was detained by US forces in Afghanistan following a firefight during which he allegedly threw a grenade that killed an American solider.

During the four-hour shootout Khadr was shot twice in the back and littered with shrapnel, blinding him in one eye.

In October 2002, following a brief stint at the Bagram detention facility where he received medical treatment, Khadr was transferred to the Guantanamo Naval Base.

Today, at age 24, Khadr has spent a third of his life at Guantanamo.

Khadr claims that, while detained at Bagram and Guantanamo Bay, he was subjected to a variety of abuses including stress positions, suffocation, sleep deprivation, being used as a "human mop" to wipe up his own urine and threatened with torture.

The prosecution case relies on statements made by Khadr to his interrogators and videotape footage found in the place where the firefight happened.

The defence had unsuccessfully sort to suppress certain of Khadr's statements, and the videotape, as being the product of torture and the fruit of the poisonous tree.

Army Col. Patrick Parrish dismissed the suppression motion on August 17 finding that there was no credible evidence Khadr was ever tortured and that although he had been told a "fictitious" story by one of his interrogators, no statements offered against Khadr were derived from, the product of, or connected to that fictitious story.

One of Khadr's Canadian lawyers, Nate Whiting, disputed the validity of Col. Parrish's findings, saying that the presiding officer must have been "listening to different evidence to the rest of us".

The ruling summarises the "fictitious" story as being ...

"about a detainee, an Afghan male, who lied to interrogators and was sent to a US prison for lying. There were 'big, black guys' in the prison. The Afghan male was a kid away from home who they could not protect. The Afghan male got hurt when the 'big, black guys' raped him in the showers."

Khadr's claim that he attempted to give all subsequent interrogators what they wanted to hear because of earlier events was discounted completely.

Just how does a 15-year-old Canadian citizen became involved in armed conflict in Afghanistan with the US forces, find himself being told "fictitious" stories in the Bagram detention centre and detained at Guantanamo Bay under the guise of the "worst of the worst"?

One of the factors at play is that Khadr is the son of Ahmed Said Khadr, who had close ties to a number of militant and Mujahedeen leaders, including Osama bin Laden, and was himself accused of being a "senior associate" and financier of Al Qaeda.

The testimony given by prosecution witnesses during the hearing of the suppression motion revealed that, as a child, Khadr played with the children of Osama bin Laden, was ordered to act as a translator for his father's Al Qaeda associates and toured around Afghanistan with his father visiting weapons training camps or guesthouses between the ages of nine and 11.

These circumstances could be construed to favour the view that as a child Khadr "voluntarily" committed murder for ideological reasons but, more reasonably, lend support to the view that he as a child he was forced by his father to assist his father's Al Qaeda associates.

In either case, Khadr is possessed of the complex duality of victim and perpetrator.

A third alternative is that Khadr has not committed the offences to which he has pleaded guilty, as his military defence team has argued, based on prosecution photographs of the scene. In that case, he is a most unfortunate victim. Coomaraswamy: Khadr should be released from custodyThe US government's decision to proceed with Khadr's prosecution has brought outcry from human rights advocates and the international community. The UN Special Respresentative of the Secretary General for Children and Armed Conflict, Radhika Coomaraswamy, has given a statement to US military prosecutors condemning Khadr's prosecution:

Coomaraswamy: Khadr should be released from custodyThe US government's decision to proceed with Khadr's prosecution has brought outcry from human rights advocates and the international community. The UN Special Respresentative of the Secretary General for Children and Armed Conflict, Radhika Coomaraswamy, has given a statement to US military prosecutors condemning Khadr's prosecution:

"The statute of the International Criminal Court makes it clear that no one under 18 will be tried for war crimes, and prosecutors in other international tribunals have used their discretion not to prosecute children. Since World War II, no child has been prosecuted for a war crime. Child soldiers must be treated primarily as victims and alternative procedures should be in place aimed at rehabilitation or restorative justice.

Even if Omar Khadr were to be tried in a national jurisdiction, juvenile justice standards are clear; children should not be tried before military tribunals."

Coomaraswamy has further urged that Khadr should be returned to Canada and not be further imprisoned in the US.

While most national legal systems prosecute juvenile criminal offenders, the decision to prosecute Khadr before a military tribunal is extraordinary.

Khadr's plea bargain removes a potential embarrassment for the US - in that it will now not have to conduct a "trial" of a boy soldier under military commission conditions.

In any event, we are served up a child victim as the contemporary representation of the "worst of the worst".

Stephen Keim

Katherine McGree

Australian Lawyers for Human Rights