The debate about the appointment of Qld CJ Tim Carmody ... Appointing a lesser candidate raises the concern that the choice was all about political favours ... Judicial independence skewered ... Unseemly spectacle ... Lapdog routine from local newspaper ... Stephen Keim and Alex McKean examine the debating tricks and bald assertions

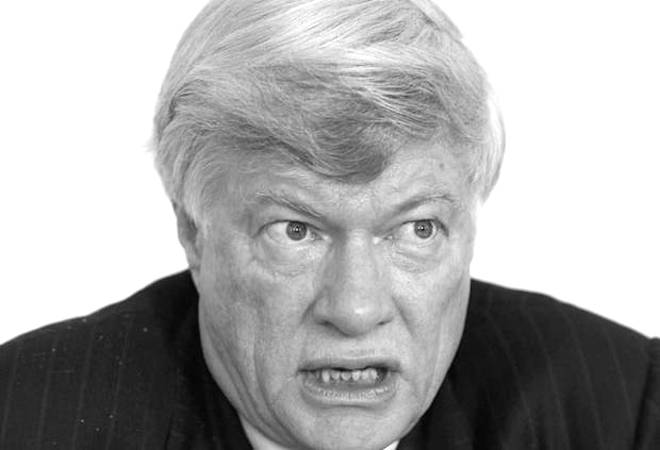

Carmody: called his independence into question by having to assert it

Carmody: called his independence into question by having to assert it

THE quality of public debate is a measure of the health of the polity. We all have a responsibility to contribute to the debate in a way that advances principles and enlightens rather than muddies public understanding of issues.

The government is ranged against the citizen in the courts, every day of the year - in criminal matters; in civil matters; in matters of taxation.

Having judges that fearlessly apply the law independent of government pressure is a key means by which our freedoms and rights are kept safe. Safeguarding the independence of the courts and the judges that staff them is, therefore, a matter of prime importance. On such a topic it might be expected that our newspapers and politicians would perform at their principled best.

The debate over the proposed and eventual appointment of the Chief Magistrate, Judge Carmody, as the new Chief Justice of Queensland, provided a proper opportunity for a high quality debate to proceed. Unfortunately, one side missed their cue.

Here we seek to examine that debate, setting out some of the main criticisms raised against the then prospective appointment and then considering what was said in response both by the government and by the Courier-Mail, which generally is supportive of the government position.

On June 13, 2014, Walter Sofronoff QC, former solicitor general, criticised the proposed appointment on the ABC program, 7.30. Sofronoff described Judge Carmody as a person who had, by his own actions, identified himself too closely with the government.

Sofronoff: CJ lacked eminence

Sofronoff: CJ lacked eminence

Sofronoff indicated that Judge Carmody lacked eminence as an advocate, having been absent from much of the major litigation that attracted the most eminent and sought after advocates. Sofronoff's short hand measurement of this quality was the limited (indeed, but one occasion) extent to which he and Judge Carmody had been opposed in major cases.

The former solicitor general also called into question Judge Carmody's need to publicly state his independence on the day his appointment was announced. He spoke of Judge Carmody campaigning on radio like a politician and asserting his suitability for the position.

Each of these criticisms raised different ways in which the proposed appointment represented a danger to the independence of our judges.

The perception that Judge Carmody had identified himself with the government was able to be gained both from the post announcement campaigning statements and from comments that he had made, in support of controversial government policies, while serving as chief magistrate.

It is not difficult to see why statements by a serving or prospective judge going to bat for a government on sticky political issues raise the legitimate fear that the appointee is not and will not be independent of that government.

The lack of eminence as an advocate also raises the concern that the appointee may not be independent. The position of chief justice is the pinnacle of the state judicial system. It calls for and it deserves the best of the candidates available.

Opinions may differ on who is the very best. But, appointing an obviously lesser candidate raises the fear that the choice is about personal or political favours and that judicial independence will be lost either because an appointee is a friend of the government and their belief that they would owe something back to the government, or the party, or the minister.

It also has the potential to send messages to candidates for judicial selection or promotion in the future that being an ally of the government in power is the way to get favourably noticed.

The third of the criticisms brings both concerns together. Declaring one's independence, "protesting too much", seems like an acknowledgement of that moral debt. To make the declaration as part of a political campaign in support of the appointment reinforces the impression that candidate and government are much too close.

On June 19, comments by Justice John Muir of the Queensland Court of Appeal were reported in the Brisbane Times. It was quite unprecedented that a serving judge would join in such a controversial debate. There is a sense that the concerns that led Justice Muir to take this dramatic step were shared by many of his fellow judges.

Justice Muir called on Judge Carmody to withdraw, citing the obvious lack of support from the other judges of the court. Muir also focused on Carmody's conduct since the announcement of his appointment as chief justice.

Muir JA: unprecedented for a serving judge to join issue with the appointment of the CJ

Muir JA: unprecedented for a serving judge to join issue with the appointment of the CJ

For example, Justice Muir criticised Judge Carmody's radio appearances describing them as an "unseemly spectacle".

Justice Muir said, if Judge Carmody had acted as a chief justice should and demonstrated independence, he would not have "effectively supported" the actions of the executive by "publicly talking up his credentials", adding that ...

"Ironically, the chief magistrate, when asserting his independence, was engaged in conduct that called it into question."

During the round of radio interviews, Carmody had said he did not possess the same "intellectual rigor" of some of his colleagues. Muir jumped on this admission, saying litigants would expect and appreciate the application of intellectual rigor.

The appeal judge had raised the same themes as Sofronoff. The antithesis of independence, closeness to government, had been demonstrated in the political act of campaigning in support of one's own candidacy.

Admissions of lack of intellectual rigour, almost an essential judicial requirement, heightened the spectre of the appointment as a political favour. Lack of support by the rest of the judges has this implication. It suggests that the criticisms being made are likely to be valid in that they are shared by a number of people who are in a good position to judge.

Tony Fitzgerald QC has been a trenchant critic of the Newman government. Fitzgerald has also publicly criticised the Beattie and Bligh governments in 2009, saying that Queensland was in danger of "slipping back into its dark past".

On July 25, the Brisbane Times published a statement by Fitzgerald, by which he became a third distinguished commentator to express concerns about what the proposed appointment meant for judicial independence.

Fitzgerald: Queensland in danger of slipping back into its dark past

Fitzgerald: Queensland in danger of slipping back into its dark past

Fitzgerald took the track record of non-independent conduct back to the period shortly before Carmody received his appointment to the position of chief magistrate. He drew attention to the then Mr. Carmody's role as commissioner of what was known as the Child Protection Inquiry and what Fitzgerald described as the "politically charged" recommendation that the entire Goss cabinet should be considered for prosecution for actions taken 20 years earlier.

Fitzgerald expressed his concern that, in the absence of a proper explanation by the government, Carmody's appointment as chief justice would raise doubts about judicial independence which will blight Queensland's legal system "for years to come".

Accepting the unusual nature of Justice Muir's decision, as a serving judge to join the discussion, it is salutary to note that it receives support from London based Australian human rights lawyer, Geoffrey Robertson QC.

Robertson: judges have a duty to speak up on matters affecting their independence

Robertson: judges have a duty to speak up on matters affecting their independence

His recent report for the International Bar Association's Human Rights Institute, Judicial Independence – some recent problems, states that judges have understandable reticence about commenting on political matters but that, on the subject of judicial independence, "they must be heard". Robertson concluded:

"It is actually the duty of every judge to speak out - in a judgment, a lecture, a book launch or even a broadcast to the nation - whenever they have reason to believe that judicial independence is under threat. Whenever and wherever this happens, the IBA should launch an authoritative enquiry into the claim, and give all possible support to a beleaguered or vulnerable judiciary."

The responses produced by Judge Carmody's defenders from the government and at the Courier Mail failed to acknowledge the importance of judicial independence either as extolled by Robertson, or at all.

Instead, the government and Courier Mail chose to defend Carmody's appointment on the basis that he is a "self made and knock about bloke" who has come from a "hard working, working class background".

In announcing the appointment, for example, the attorney general had stated that Judge Carmody had grown up in a housing commission house in Inala, and had worked as a meat-packer and police officer, prior to becoming a lawyer.

Having risen from modest beginnings, or having overcome disadvantages can be an advantage to a judge. Equally, having judges appointed from a variety of backgrounds can be of assistance to the judiciary as a group. A variety of perspectives can help avoid the law being interpreted and applied from the viewpoint of a single prism.

One's background, however, does not in itself provide the expertise needed to perform the job of a judge or, indeed, any job.

Neither do Carmody's qualities, as trumpeted by his government supporters, dispel the concern that he was among the lesser candidates for the job in terms of potential judicial ability. The argument remains that the favour he has received by becoming the chosen one will impact upon his perceived and real independence from those who bestowed that favour.

By discussing the matter as if it were a form of beauty contest and emphasising knockabout qualities, the defenders almost acknowledge the validity of the criticism that Judge Carmody was, indeed, far from the best candidate.

It is difficult to reconcile some of the comments made by the government in defence of Carmody with the available evidence. On June 17, Premier Newman said it was incorrect to suggest that no one in the judiciary supported Carmody's appointment. Even if the premier was to have identified some supporters of the candidate, it would do little to meet the essential concerns about the harm to judicial independence raised by the critics.

The further problem is that Newman's bald claim is inconsistent with Carmody's own admission that none of the other Supreme Court judges contacted him to congratulate him on his appointment and the fact that they did not attend the new chief justice's public elevation ceremony.

* * *

THE editor of the Courier Mail, Christopher Dore, published on June 20 a lengthy editorial about the appointment of Carmody.

Dore, initially, tried to avoid meeting the principled criticisms made against the appointment by categorising all the complaints as "private boys' club complaints about seniority". These were not the concerns raised against the appointment.

Dore: local Murdoch man

Dore: local Murdoch man

Dore then correctly identified the criticism that Judge Carmody was "politically tainted", but he then engaged in the old debater's trick of attributing all of the appointee's self-imposed political taint as being due to his having instructed other magistrates to "enforce the letter of laws the Newman government passed".

He sought to defend Carmody's administrative directive, stating that the chief magistrate "is charged with administering the law of the land, regardless of personal views".

Dore's categorisation of the directive is much too kind. Leaving that aside, what the debater's trick seeks to do is conveniently forget the numerous other times in which Carmody had been identified as casting himself much too close to the executive by airing his personal views.

These occasions include his public support for the government's controversial "anti-bikie" laws; publicly supporting the embattled attorney general over his leaking of confidential discussions; and his public campaign supporting the choice of himself as chief justice.

The debater's trick seemed to have exhausted Dore's attempt to meet the sting of the actual criticisms. His next argument was to say that he who wields the power is in the right. That is, the Supreme Court bench is comparable to any other workplace and that the premier, as the employer, should have the final say as to who should be appointed.

This ignores the context that the debate was not about whether the executive had power, but about what was the correct or appropriate way to exercise the authority in question.

The argument also ignores the obvious fact that many a workplace; corporation; and, even more importantly, football team, has been ruined by the boss appointing useless mates to top jobs.

What should editor Dore do if all his senior journalists are deeply concerned about a decision that he, as boss, is about to make. Should a wise boss not stop to ask about the cause of that deep concern held by many conscientious people?

Essentially, Dore is saying that concerns about judicial independence are neither here nor there. The premier is boss and he can ram through the appointment no matter what harm it might do to our erstwhile independent judiciary.

The editor went into print again on the topic on July 31. This time, the line was "move on, there's nothing to see here".

Rather than meeting the arguments that appointment by favour (as opposed to merit) and appointment of a political crony are likely to damage the independence of the courts, generally, the Courier-Mail wielded the debating swear words "judicial class warfare ... [and] sour grapes".

The paper quoted a legal academic who suggested that Justice Carmody's experience and skill were comparable to "two or three appointments" made by the previous Labor government. It should be noted that the previous chief justice was not appointed by a Labor government.

Dore concludes by posing the question: what harm can there now be in putting an end to this unedifying circus and just letting Justice Carmody get on with the job, for better or worse?

This is the terrifying question.

Will the government, having won through on the appointment of the CJ, after cooling its heels for a while, get on with the task of recasting the judges of Queensland in its own image so that every judicial officer feels that they must do what the people (that is, the premier) expects?

Or will the government be suitably chastened by the political bloody nose it has suffered from the debate and approach future judicial appointments with great respect for the institution and a concern for its role in protecting the rights of all of us?

Will the new chief justice, after a period of quiet reflection, regard his new position as simply a grander pulpit to that which he enjoyed as chief magistrate and from which he can continue to make statements similar to those which attracted criticism of the appointment?

Alternatively, he might take his own promises to be fearlessly independent to heart and strive, despite his self-acknowledged shortcomings, to be the best chief justice he can be?

That is, will the damage be as bad as feared or has the willingness of good people to speak-up limited the damage to our polity?

If the happier alternatives ensue, credit will be to those like Sofronoff, Justice Muir and Fitzgerald who stood-up for the principle of fearlessly independent judges.

No thanks will go to those who ignored the principle that was under threat and who sought to meet principled criticisms with debater's tricks, political swear words and bald assertions.

Stephen Keim and Alex McKean