Pressing questions ... Is Assange a journalist, a publisher, a combatant in information warfare, a tool of Russia? ... Do journalistic standards apply? ... Does it matter? ... The superseding indictment ... The Espionage Act and the First Amendment ... Lacunae in the law ... Janek Drevikovsky explains

Is Assange a journalist?

The law is unhelpful

American federal law gives no definition of what counts as a "journalist".

Garrett Epps, a professor of constitutional law at the University of Baltimore, told the Washington Post that it was "a strange twilight zone in terms of the Constitution" and said the Supreme Court had never clearly defined what was meant by "journalism".

Jameel Jaffer, director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, agreed.

"The courts haven't extended any protection to journalists that they haven't extended to the public at large," he said. "This is in part because extending special protections to journalists would require the court to say who's a journalist and who isn't."

For example, in Obsidian Finance Group LLC v Cox, the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit held that

"The protections of the First Amendment do not turn on whether the defendant was a trained journalist, formally affiliated with traditional news entities, engaged in conflict-of-interest disclosure, went beyond just assembling others' writings, or tried to get both sides of a story."

So whether or not Julian Assange is a journalist doesn't depend on the law. It depends on your own definition of what is meant by journalism and journalist.

Definitely a journalist

Barry Pollack, a lawyer for Assange, thinks the relevant test is the publication of information that is "truthful" and "in the public interest".

"I do not find the question of whether he is a journalist a tricky one," he told the Washington Post. "Mr. Assange publishes truthful information that is of public interest. I think that is a pretty good definition of 'journalist'."

Pollack has elsewhere sought to explain the allegations against Assange as basically analogous to cultivating a source.

"The factual allegations ... boil down to encouraging a source to provide him information and taking efforts to protect the identity of that source."

Definitely not a journalist

Greste: journalism is not a matter of dumping untiltered information on the internet

Greste: journalism is not a matter of dumping untiltered information on the internet

Peter Greste, famously imprisoned for his reporting in Egypt, scoffs at the idea of Assange being a journalist.

He prefers to define "journalist" with reference to the tricks of the trade - curation and presentation chief among them.

"Journalism demands more than simply acquiring confidential information and releasing it unfiltered onto the internet for punters to sort through. It comes with responsibility.

To effectively fulfil the role of journalism in a democracy, there is an obligation to seek out what is genuinely in the public interest and a responsibility to remove anything that may compromise the privacy of individuals not directly involved in a story or that might put them at risk.

Journalism also requires detailed context and analysis to explain why the information is important, and what it all means."

To Greste's mind, Assange did none of these things. He dumped a cache of documents online, secret identities and safety be damned.

Other releases of leaked information have been very different, Greste says.

"When The Guardian and The New York Times got hold of the cache of files that Edward Snowden downloaded from the US National Security Agency in 2013, they spent months searching through it to pick out the documents that exposed the extent of the NSA's surveillance operations.

Then, the newspapers took months more to release those stories in a cascade that was as explosive as it was impressive."

Greste thinks this is a far-cry from Assange's indiscriminate releases, and so a journalist Assange is not.

Kathy Kiely and Laurel Leff, two American journalism academics, tentatively agree with Greste.

Writing in The Conversation, they argue that what sets journalists apart is "standards".

"In insisting that journalists should not be prosecuted for disclosing classified information or for refusing to reveal confidential sources to grand juries, the press is seeking a privilege in both the legal and literal meaning of the term.

It's not a privilege if everyone gets it. There has to be something special about what journalists do, and how and why they do it, that makes them worthy of a privilege that others don't receive."

Their point seems to be that Assange fell below that standard, though they don't explain exactly how, although they do say:

"As a profession, journalists are becoming increasingly aware of the need to advocate for, and try to uphold, standards that differentiate them from those who merely make information available."

A tool of Russia

Eli Lake, writing for Bloomberg, thinks that Assange might have been a journalist, or something close to it, when he started publishing his Wikileaks cache.

"When Assange founded WikiLeaks, its mission was to expose authoritarian governments. As he told potential collaborators in 2006, according to the New Yorker, 'Our primary targets are those highly oppressive regimes in China, Russia and Central Eurasia'.

In those early days, WikiLeaks published all kinds of damaging information against all kinds of targets, from Somali Islamists to the Chinese government. Much of it was in the public interest.

And even in 2010 when Assange helped Manning steal and transfer the State Department cables it later exposed, he worked with media organizations to report out the raw material his source provided."

Manning: stole and transferred cables for Assange

Manning: stole and transferred cables for Assange

But later, Lakes writes, Wikileaks started to turn its efforts against the United States, often as a kind of Russian pawn.

"By 2016 though, WikiLeaks was not so much a publisher as it was a combatant in information warfare. Mueller alleged that WikiLeaks in that year published the fruits of Russian hacking to influence the 2016 presidential election.

Then a year later, WikiLeaks disarmed key tools of the CIA, one of the agencies charged with defending against these kinds of Russian hacks."

Practically, Assange should not be defined as a journalist

Kieley and Leff, the academics writing for The Conversation, think that, practically speaking, we shouldn't even want to fit Assange within the category of journalist. The consequences for the rest of the media would be bad.

Rushing to make Assange a media "poster boy" will only invite hostile authorities to take a tougher stance against the industry as a whole, the academics write.

Prosecuting Assange will harm the media even if he isn't a journalist

Whether or not he is a journalist, strictly, the kind of things Assange is charged with are the bread and butter of journalistic practice.

As Carrie DeCell, a lawyer with the Knight First Amendment Institute, tweeted:

But for the most part, the charges against him broadly address the solicitation, receipt, and publication of of classified information. These charges could be brought against national security and investigative journalists simply for doing their jobs, and doing them well. 6/x

— Carrie DeCell (@cmd_dc) May 24, 2019

If Assange is convicted, the precedent for real journalists will not be a good one.

What are the charges? To which publication do they relate?

Original indictment

When Assange was first indicted, he faced charges of conspiracy to commit "computer intrusion".

The charge fell under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. It was a conspiracy charge and alleged that Assange agreed to work with whistleblower Chelsea Manning to crack a password and access higher-level classified documents.

The hacking-efforts (which were unsuccessful) occurred in early 2010, around the time that Wikileaks released its Afghan and Iraq files.

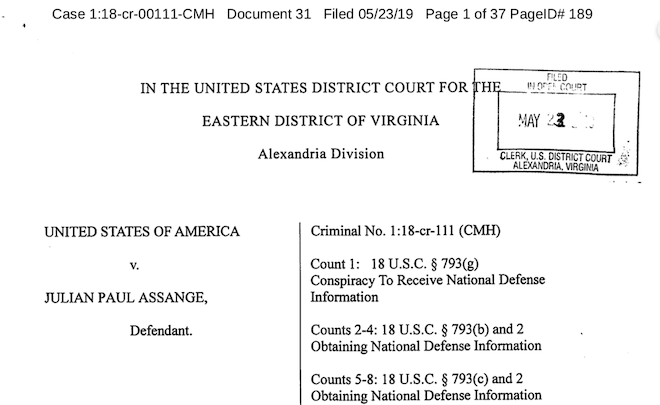

Superseding indictment

Then, in May 2019, a Virginian grand jury issued a superseding indictment.

That indictment carried a further 17 charges against Assange, and also retained the computer intrusion charge from the original indictment.

The 17 new charges fall under the Espionage Act of 1917.

Under that Act, anyone who obtains secret documents relating to American military or security interests is guilty of a crime.

And anyone who discloses or communicates that information is guilty of another offence.

Assange is charged with conspiracy to obtain, actually obtaining and disclosing a variety of different security, sensitive documents.

All counts relate to Assange's efforts in late 2009 and early-to-mid 2010.

Several of Wikileaks' 2010 releases are in play: files relating to US troops' rules of engagement in Iraq; state department cables; and briefs on those detained in Guantanamo Bay.

Crucially, Assange is now charged not just with obtaining information illegally; he is also charged with disclosing, that is publishing, that information.

This development comes close to criminalising normal journalistic practice.

No charges relate to the Wikileaks publication of the Russian hacked emails to and from John Podesta, Hillary Clinton's 2016 campaign manager.

Can the First Amendment help Assange?

The First Amendment protects the freedom of speech and the press from incursion by federal or state law.

But someone who leaks information in a breach of the Espionage Act is not protected by the first amendment. There is ample authority to that effect.

In United States v Morison, the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit was content for a navy intelligence officer to be convicted for leaking classified photos to a defence journal.

And famously, Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo, the leakers in the Pentagon Papers affair, were charged with espionage, theft and conspiracy. However, the charges were dismissed by a federal judge after Ellsberg's psychiatrist's rooms were broken into.

Whistleblowers: Russo and Ellsberg - court ordered a mistrial

Whistleblowers: Russo and Ellsberg - court ordered a mistrial

These cases concerned the leaker of information, but Assange is charged not as a leaker, but as a publisher.

No United States Court has ever ruled on whether someone can be punished for publishing material in violation of the Espionage Act.

A Congressional research paper concluded the question was "open". So it may not be of assistance for Assange's fiancée Stella Morris to describe her partner as a "publisher".

Does the Pentagon Papers case help?

The Pentagon Papers case did not, of course, decide whether publishing illegally-obtained information could be punished.

It was a case about prior restraint - that is, about whether the federal government could enjoin the Times and Post from publishing.

Assange is being prosecuted for decades-old publications; there is no question of prior restraint - this is about punishment.

In fact, in the Pentagon Papers case, a majority of the court, in various obiter dicta thought the news outlets could be punished.

For example, after listing a series of statutes that might have criminalised publication of the papers, Justice White said:

"I would have no difficulty in sustaining convictions under these sections on facts that would not justify the intervention of equity and the imposition of a prior restraint."

Justices Marshall and Stewart, as well as the three dissenting judges (Chief Justice Burger and Justices Blackmun and Harlan) said much the same thing.

Will the US government try to get around the First Amendment?

It seems likely.

During Assange's extradition hearing, counsel for the US government seemed to argue the First Amendment would not stand in the way of a prosecution.

In a transcript taken down by former diplomat Craig Murray, James Lewis QC cross-examined Eric Lewis, a lawyer from Washington firm Lewis Baach Kaufmann Middlemiss.

Lewis QC: for the US government

Lewis QC: for the US government

Appearing as an expert witness, Eric Lewis argued prosecuting Assange would be impossible because of the First Amendment.

But James Lewis had other ideas:

James Lewis QC: A close reading of the Pentagon Papers judgment shows that the New York Times might have been successfully prosecuted. Three of the Supreme Court judges specifically stated that an Espionage Act prosecution could be pursued for publication.

Eric Lewis: They recognised the possibility of a prosecution. They did not say that it would succeed.

James Lewis QC So your analysis that there cannot be a prosecution of a publisher on First Amendment grounds is incorrect.

[snip]

Eric Lewis: There has been an unbroken line of the practice of non-prosecution of publishers for publishing national defence information. Every single day there are defence, foreign affairs and national security leaks to the press. The press are never prosecuted for publishing them.

James Lewis QC: The United States Supreme Court has never held that a journalist cannot be prosecuted for publishing national defence information.

Eric Lewis: The Supreme Court has never been faced with that exact question. Because a case has never been brought. But there are closely related cases which indicate the answer.

James Lewis QC: Do you accept that a government insider who leaks classified information may be prosecuted?

Eric Lewis: Yes.

James Lewis QC: Do you accept that a journalist may not aid such a person to break the law?

Eric Lewis: No. It is normal journalistic practice to cultivate an official source and encourage them to leak.

Does a First Amendment argument stand a chance?

On the Espionage Act charges, the experts are divided.

Gary Ross, an assistant professor at the Daniel Morgan Graduate School of National Security, thinks that a First Amendment defence doesn't stand a chance.

That's because the courts will often allow breaches of the First Amendment if the aim is to protect national security.

In Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, for example, the Supreme Court held that it did not violate the First Amendment to prevent an aid group from sending educational material to terrorist organisations.

In his article, Ross notes that on matters of security, the courts usually defer to the executive arm.

In Holder, the court found the executive was "uniquely positioned" to determine what would harm the national interest and what would not.

Ross suggests a federal court would be similarly deferential in Assange's case.

Assange's defence would be difficult, because he would struggle to show that the public interest in his leaks outweighed national security concerns.

That's because of the presence of unredacted names and "un-newsworthy" operational information, whose publication only served to endanger lives.

Holder found that the government did not have to definitely show that a publication had or would cause harm: all that was necessary was an "informed judgment" that it had or would.

It might not be necessary, Ross thinks, for the US government to prove someone had actually died as a result of Assange's leaks.

Yet, other experts think a First Amendment defence would succeed.

James C. Goodale, former general counsel to The New York Times, argues that the amendment applies to Assange's case.

However, he thinks its application should not be through an "ad-hoc" balancing of public interest with national security concerns.

Rather, Goodale says the "clear and present danger" test, developed in the Pentagon Papers case, is the right one to use.

Assange's publishing - and also his newsgathering, Goodale says - would be protected unless the government could prove it posed an imminent threat to security.

Goodale seems to doubt the government could do so.