Vic Bar readers' course and exam ... Monstrously hard exam with high failure rate ... Clogged course ... Bulging waiting lists ... Skewed demographic of bar entrants ... The overflow ... Barriers to entry ... Joseph Friedman reports

Pass mark is 75%

Pass mark is 75%

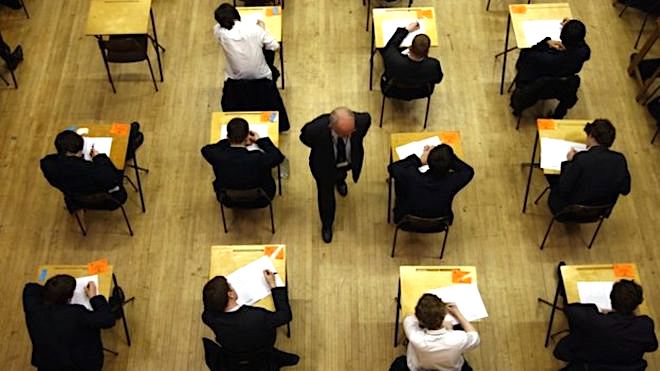

On a wet, chilly Sunday three weeks ago, over 200 aspiring advocates sat the Victorian Bar exam. The scores will be released sometime in December, but one result is already known: most of the applicants will fail.

The Victorian Bar Exam is notoriously difficult, with a fail rate of between 60-70 percent. Applicants need 75 percent to pass the three hour test, a requirement that, according to Victorian Bar Council President Róisín Annesley KC, provides "security for the public" that any new barrister has a base level of ability for both advocacy skill and legal knowledge.

Neither Annesley nor any of her contemporaries sat the bar exam, which was first run in 2011. Annesley is quick to acknowledge that the absence of an exam did not prevent her from having a successful career. "But I think it's here to stay," she tells Justinian.

Bree Ridgeway is one of those aspiring advocates who sat the test last month. Ridgeway, 33, works as an associate to a judge of the Supreme Court.

She is also undertaking a PhD in philosophy, yet describes the bar exam as "uniquely stressful". Ridgeway says the culture of the exam, and the intense study required, "harkens back to law school days".

"You hear stories about people studying insane amounts for years in advance, and that feeds into the terror that you're not doing enough yourself."

According to the Bar Exam Course - a private, $2,200 program designed by Melbourne barrister Caitlin Dwyer to help applicants Pass The Bar, The First Time - candidates "can be working full-time but should have at least 20 hours each week to devote to studying for the bar exam".

Twenty hours each week.

An inordinate amount of time for any full-time employee let alone a lawyer, for whom the ordinary 40-hour working week is fanciful. And a key reason why several people Justinian spoke to believe that the exam risks homogenising the bar.

As a Supreme Court associate, Ridgeway has eight weeks of annual leave and rarely works outside of 9-5, Monday to Friday.

She says an associateship is the ideal job to have while studying for the bar, and Annesley tends to agree.

"Because there is a need for study, we do get a lot of associates," Annesley says, "... maybe we get fewer older candidates."

While associateships are highly sought after, they also pay poorly, skewing the demography towards those who are young, relatively privileged, and with few responsibilities.

The risk for the bar is that the burdensome entry requirement will cause a similarly skewed demographic.

"Of the people that I know who have passed, everyone has been 25-early 30s ... [with] pretty privileged backgrounds," Ridgeway says.

For candidates with dependants, or those required to work longer hours, "I really don't understand how [they] could physically get the amount of work done that you need to do to get it done."

In 2014, a review of the bar exam chaired by Michael Wheelahan QC (now Justice Wheelahan of the Federal Court) analysed in detail all of the arguments for and against the exam and looked at whether its introduction had distorted the demography of those coming to the bar.

The review is proprietary to the Victorian Bar, which was not inclined to provide Justinian with a copy.

Annesley has not recently looked at the review, and is unaware of the socio-economic status of new additions to the bar, but she tells Justinian that its make up is "reflective of [the] demographic of people coming out of law school as a whole", with more females than males, and much greater ethnicity than in the past.

She adds, there has "always been a certain amount of need for savings and planning" since the readers' course was introduced in 1979.

The readers' course is an eight-week affair commencing in March and September each year. It is arduous (Monday to Friday, 8:00am – 6:00pm) and expensive ($7,000), but much lauded, taught by top barristers as well as some judges, all volunteers.

Before the introduction of the exam, admission to the readers' course (approximately 40 people in each course) was determined on a first-in, first-served basis.

Those who missed out would be placed on a waiting list, and the course began to fill up years in advance.

Concerned by the overflow, and for other unrelated reasons, in 2009 the Bar Council commissioned a review of the course, which resulted in a separate report recommending the introduction of an exam.

By adding a barrier to entry, and increasing the number of readers to 48 per course, the bar hoped to get rid of the waiting list.

"It's not really achieving what we want it to achieve," says Annesley.

Annesley: the bar is fantastic

Annesley: the bar is fantastic

Despite the exam's difficulty and high fail rate, too many people are passing the exam, and some successful candidates continue to be placed on a waiting list, forced to delay the start of their practice for at least another year.

Justinian has learnt of unverified reports that there are plans in place to make the exam even harder, so as to reduce, and ultimately eliminate, the waiting list.

And yet Justinian has also heard that today's new crop of advocates - like most seasoned barristers - are tremendously overworked, particularly in crime, where demand for counsel far exceeds supply.

Is there a better alternative?

Annesley says the bar has "looked at having more courses", but has so far been unsuccessful at finding time in the calendar.

The Bar Council's president is emphatic that the bar is "not ... confining people coming", but rather ensuring all those who do enter this vaunted and difficult profession receive the best possible training in an intimate readers' course environment.

Arguably, the effect is the same.

The number of candidates sitting the exam increases each year. As long as the bar continues to hold no more than two readers' courses per year, with no more than 48 readers per course, the number of those on the waiting list will continue to increase unless the course is made harder.

If the course's difficulty is increased, more intense study will be required, further favouring those with time and money to spare.

That result is undesirable for all involved.

Annesley tells Justinian that the "the bar is a fantastic place" and "encourage[s] everyone to come".

She and her team review the exam and the readers' course each year, consistently adapting to improve aspiring advocates' experiences.

Yet with fewer than 100 new readers annually, most of those aspiring advocates who heed the president's call will find themselves looking for work elsewhere.