The ambivalence of friendship

Critics Corner •

Critics Corner •  Tuesday, April 12, 2011

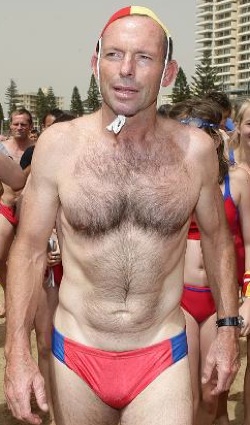

Tuesday, April 12, 2011 Michael Kirby's monarchist mates rarely lent a hand to help him during the great crises of his life ... Tony Abbott was a royalist chum, but did nothing to stop Heffernan's onslaught ... The High Court was paralysed ... Gleeson and Gaudron shouting match over whether to support Kirby ... Review of impressive new biography, Michael Kirby: Paradoxes and Principles Her Majesty: ably assisted by Howard, Abbott and KirbyMichael Kirby fought so hard to assist Tony Abbott and John Howard to keep the Queen firmly in place as the monarch of Australia - so you'd think they might have lifted a finger to help him at crucial times.

Her Majesty: ably assisted by Howard, Abbott and KirbyMichael Kirby fought so hard to assist Tony Abbott and John Howard to keep the Queen firmly in place as the monarch of Australia - so you'd think they might have lifted a finger to help him at crucial times.

Not a bit of it.

A.J. Brown's fascinating biography of Kirby (Michael Kirby: Paradoxes and Principles, The Federation Press) shows that an enduring love of The Queen is not something that binds royalists when the chips were down.

At the time Kirby was falsely accused by Senator Bill Heffernan of using Commonwealth cars to ferry rent boys to and from his home, the High Court judge wrote to monarchist colleague Lloyd Waddy, saying that he had been "rather disappointed" that Abbott's response had been biased in favour of Heffernan.

It was understandable that Kirby was a bit hurt by this. After all, he had helped Abbott develop important aspects of his political platform.

Publicly, Abbott was sitting on the fence. He loved the monarchist part of Kirby but was far less enthusiastic about the homosexual part. (This is strange, because the monarchy is a gay honey-pot.)

After a speech in 2000 about homosexuality that the judge made to boys at St Ignatius College, Riverview, Abbott wrote to him saying he had trouble with the idea that homosexuality should be regarded as acceptable, rather than simply accepted, "especially when the overwhelming weight of tradition holds that it is in some sense sinful". Abbott: on the fenceAs early as May 2001 Kirby had warned Abbott, who was then a senior minister, that anyone who listened to the Comcar rumours needed to take a "reality check".

Abbott: on the fenceAs early as May 2001 Kirby had warned Abbott, who was then a senior minister, that anyone who listened to the Comcar rumours needed to take a "reality check".

That warning was made during an Empire Day celebration at the Canberra flat of Julian Leeser, another monarchist and Abbott staffer. (It does seem quaint that Empire Day is still celebrated in some quarters.)

After Heffernan's allegations were shown to be a concoction of falsities and the senator offered his insincere apology to Kirby, Abbott rang the judge and said that there should be proper recompense for what had occurred.

Kirby said that should be in the form of an amendment to the Judges' Pensions Act, to recognise the relationship with his lifelong partner, Johan van Vloten.

A month later Kirby received this reply from Abbott:

"Rest assured that - at the highest levels of government - there is a great deal of fellow-feeling for you at this time ... I know how strongly you feel on the superannuation issue. For myself, I have always been torn; on the one hand, not wanting to accept an equality with marriage; but on the other, not wanting to deny what could be described as an ordinary right. I'm afraid I have not resolved this in my own mind and doubt that the government would be ready to change the longstanding rules... There is a general acknowledgement of the great wrong you have suffered but no clear view as to how things can be made good."

Not much joy there.

It was not until early in the life of the Rudd government that parliament amended the Judges' Pensions Act to provide for pensions to be payable to surviving same-sex partners of Commonwealth judicial officers.

Kirby was now liberated and free to retire from the High Court, which he did on February 2, 2009.

Abbott wrote him another of his curious notes:

"Michael - Tributes have been pouring in. The one dubious tribute was the claim that you might have chosen politics. I suspect that would have made you the only really straight politician."

Kirby: urged Abbott to take a "reality check"Kirby replied:

Kirby: urged Abbott to take a "reality check"Kirby replied:

"To be called a 'really straight' anything is a bit confusing to me - but I won't go there in case I embarrass you."

Anyone that knew Heffernan knew he was obsessed about Kirby and his sexuality. He had been fulminating and scheming for years about how to effectively damage the judge.

Heffernan was in regular contact with journalists about Kirby, his homosexuality, his use of Commonwealth cars and allegations of using rent boys from Darlinghurst.

A.J. Brown doesn't state this in the book, but I would venture that like any plugged-in person in the political-media echo chamber Abbott knew in advance what Heffernan was planning to do to Kirby - if not in detail, certainly in broad terms.

In fact, three days before Heffernan launched his attack Abbott had been at the senator's home in Junee where he was told "something big" was about to be dropped.

Abbott said that at the time he thought, "Oh God, what can it be"?

Abbott said to Brown in interviews that Heffernan had been told the government did not support "his particular crusade".

Yet if even a cursory check of Heffernan's "evidence" had been made by Abbott he could have called upon Howard to kill the whole enterprise stone dead.

Abbott knew what was coming, yet he did nothing to try and stop it. He did nothing to dissuade Howard to back off the nasty and cynical call for an inquiry into Kirby and his mischevious remarks that "proven misbehavior or incapacity" could take "many forms and cover a lot of conduct".

Monarchists are not without their treachery.

* * *

Heffernan: sacked as Cabinet secretaryHeffernan's attack in the Senate was made on the evening of Tuesday, March 12, 2002.

Heffernan: sacked as Cabinet secretaryHeffernan's attack in the Senate was made on the evening of Tuesday, March 12, 2002.

By lunchtime on Thursday, March 14, the Chief Justice (Smiler) Gleeson, the court's registrar Chris Doogan and Kirby all knew the Comcar records were bogus.

The High Court's Marshall, Lex Howard, had been told as much by the Department of Finance and Administration.

Kirby said that in that first 48 hours after the senate assault only one of Kirby's colleagues on the court had walked the short distance to his chambers to offer direct support - Mary Gaudron.

Later on that Thursday she too learned that the documents were frauds.

At that time Gleeson, Gummow and Callinan were sitting in court. Gaudron got on the phone to Hayne in Melbourne, who agreed that if faked evidence was involved that was, in a sense, an attack on the entire court.

He supported the idea of a press release to be issued by the court supporting Kirby and saying the attack on him had been based on documents whose authenticity was in question.

McHugh agreed with the plan.

When Gleeson, Gummow and Callinan came out of court, Gaudron ushered them into her chambers to explain what was being proposed.

Gaudron told A.J. Brown that Gleeson simply "lost it":

"He was screaming at me. 'Who do you think you are? Have you appointed yourself press secretary to this court? Do you think you could issue press statements? What right did you have to go to Chris Doogan and get these?' He was furious with me. And there wasn't really a reason to be furious with me...

It was unprecedented... And I wasn't shouting, until he went off the rails, and I said: 'Get out of my chambers, I don't want to see you in my chambers again, and I won't speak to you again, but rest assured I'm going to do something about this. I'm not going to let this matter lie'."

Gaudron: told Gleeson to get out of her chambers And she didn't let it lie. She phoned her friend Trish Kavanagh, a judge of the NSW Industrial Relations Commission and the wife of Labor frontbencher Laurie Brereton.

Gaudron: told Gleeson to get out of her chambers And she didn't let it lie. She phoned her friend Trish Kavanagh, a judge of the NSW Industrial Relations Commission and the wife of Labor frontbencher Laurie Brereton.

She leaked the information that only a few in the public service and on the court knew - that Heffernan's documents were not authentic.

Coincidentally, Brereton realised the records must have been fake, because on a day it showed him travelling in a Comcar in Sydney, in fact he was on a family holiday in Hayman Island.

Brereton called a press conference to announce this, and Heffernan's scam was up.

In the interim, the court had done nothing for Kirby. It just sat on the knowledge the documents were bogus.

* * *

Another personal disappointment for Kirby would surely have been the job application speech made by Dyson Heydon at a Quadrant dinner in October 2002 (six months after Heffernan's attack).  Heydon: florid speechThe speech was floridly entitled Judicial Activism and the Death of the Rule of Law. Apart from getting stuck into the Mason court, the speech directly went for Kirby.

Heydon: florid speechThe speech was floridly entitled Judicial Activism and the Death of the Rule of Law. Apart from getting stuck into the Mason court, the speech directly went for Kirby.

He said that Kirby's appointment as chairman of the ALRC was a significant step in the deterioration of Australian judicial standards and that his opinions on international human rights amounted to unacceptable activism.

He called for a return to Dixonian "strict and complete legalism" and he assaulted Kirby's personal style:

"Ambition, vigour, energy and pride can each be virtues. But together they can be an explosive compound... Judgments tend to cite all the efforts of their author, of their author's colleagues, of other state courts and English courts and American courts and Canadian courts and anything else that comes to hand. Often no cases are followed, although all are referred to." etc, etc.

The speech did the trick and the Howard government appointed Heydon to the High Court vacancy left by Mary Gaudron.

Forty years earlier, when he was an Arts student, Heydon had been a member of the Sydney University SRC, of which Kirby was president.

Later he went on to become dean of the law faculty at Sydney, where Kirby had dealings with him on law reform issues.

In 1976, Kirby hired Heydon's research assistant Pamela as an ALRC researcher.

Pamela and Dyce got married and Kirby helped secure a place for their daughter at a private school.

Heydon, of course, was a monarchist and sat on the legal and constitutional affairs sub-committee of Australians for a Constitutional Monarchy.

Kirby backed Heydon's appointment as a QC.

What are friends for?

* * *

I've skimmed the surface of this compelling warts and all biography. However, I thought some elements of the book that revealed the febrile nature of friendship and collegiality were worth highlighting.

No doubt other reviewers will take you into Kirby's relationship with Michael McHugh, how the Court of Appeal in NSW tried to knobble his appointment as president, the occasions his public prosleytising overstepped the mark and left him looking embarrassed and silly, and the time the United Nations pulled the rug from under his human rights work in Cambodia.

You might even buy the book and read all this for yourself.

Michael Kirby: Paradoxes and Principles by A.J. Brown. The Federation Press. $59.95

Mary Gaudron,

Mary Gaudron,  Michael Kirby,

Michael Kirby,  Murray Gleeson,

Murray Gleeson,  undefined

undefined

Reader Comments