Voices from on High

Friday, March 24, 2023

Friday, March 24, 2023 Capturing the essence of constitutional thinking ... Three former High Court judges write in favour of the Voice ... One against (three guesses) ... Overview of the principal contentions ... Justinian wields the scissors and paste pot

At least three former High Court justices - Kenneth Hayne, Robert French and Murray Gleeson - have publicly supported the proposed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Voice.

We know their grasp of the Constitution is nowhere near as firm as that of Chris Merritt from the Rule of Lawyers Institute; conservative "prominent lawyer" Louise Clegg; propagandists at The Australian; or buskers on Murdoch's After Dark (MAD).

Maybe they are drawing inspiration from former justice Ian Callinan, who is not a Voice man. [See our reprised review of his spellbinding novel The Coroner's Conscience.]

Nonetheless, now that we know the question for the proposed constitutional alteration, and the alteration itself, it is good to have the foresight of jurists with constitutional depth.

Kenneth Hayne

Writing in Guardian Australia (March 23):

Hayne: details, distractions

Hayne: details, distractions

"Are there any reasons to fear what is proposed?

The short answer is: no."

[snip]

"We have heard a lot about the 'need for detail' but it will be the parliament that decides the details about how the voice is set up and how its representations are dealt with by the parliament and the executive. And this is how it should be. The constitution sets out principles, not machinery.

"Asking for details is a distraction. It asks for a prediction of what parliament will do in the future. That is for parliament to decide."

Reiterating that it is not a third chamber of parliament and that it will not affect the powers of parliament or the executive, Hayne asks, will there be litigation?

"Answering that depends on the answers to at least three other questions. Who would bring the claim? What would they want the courts to order? How likely are they to succeed?"

What the Voice has said does not dictate the outcome.

"The courts can and do review decisions made by the executive. But the courts look only at whether the decision was lawfully made, not at the merits of the decision. That is the courts apply the rule of law – public power is not to be exercised unlawfully ...

Application of the rule of law is to be welcomed, not feared. It is the way in which the exercise of public power is kept within lawful bounds.

The change that is proposed will recognise the proper place that the First Peoples have in the long history of this land. The constitution will better reflect that ALL Australians own the constitution. And the change looks to the future by providing in our constitution that First Peoples have a voice to parliament and the executive in matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples."

Hayne is one of the constitutional advisers to the government on the Voice.

Robert French

Wrriting in Australian Public Law.

Robert French: it's not about race

Robert French: it's not about race

"The Voice is a big idea but not a complicated one. It is low risk for a high return. The high return is found in the act of recognition, historical fairness and practical benefit to law-makers, governments, the Australian people and Australia’s First Peoples.

It does not rest upon race. It accords with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples for which Australia voted in 2009. It is consistent with the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination. Suggestions that it would contravene that Convention are wrong."

[snip]

"The first constitutional element of The Voice is that it will be a ‘body’. The relevant ordinary meaning of that word is a group of people who work or act together. The only constitutional requirement in relation to the body is that it be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice."

[snip]

"Parliament could not make a law which could confer on The Voice a legal right to veto a proposed law. Parliament could not make a law limiting its own law-making powers by legally requiring prior consultation with The Voice. The Voice is not a third chamber.

"The constitutional amendment would, however, support the adoption by Parliament of internal procedures to provide for The Voice to be heard. The Parliament could also make a law requiring the Executive to have regard to representations by The Voice to the Executive when adopting or changing policies and practices relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples."

[snip]

"There is little or no scope for constitutional litigation arising from the words of the proposed amendment. The amendment is facilitative and empowering. Parliament cannot legally be compelled to make laws for The Voice. It cannot be compelled to make a particular kind of law. Nor can it be prevented from repealing or amending the laws it makes."

Importantly, French says, the Voice is not about race. "It is about our First Peoples as the indigenous people of Australia."

"... by providing for The Voice in the Constitution, the Australian people perform an act of recognition and acknowledgement of First Peoples as the bearers of the first history of our continent."

French adds that powers conferred on the parliament by the Constitution in 1901 were left to the parliament to adopt as and when necessary.

"The Voice proposal is a once in a lifetime opportunity for Australia to fill a gaping hole in our Constitution - to recognise our first history and the First Peoples who bear it and the painful legacy of its collision with the second history of colonisation."

Murray Gleeson

Writing in Inside Story (July 21, 2019)

Murray Gleeson: The Voice is a response to division

Murray Gleeson: The Voice is a response to division

"Parliamentary supremacy (not sovereignty - there is no such thing in Australia as a sovereign parliament, and there never has been) is one of the essential safeguards of our liberal democracy. It is unlikely that parliament will propose a change to the Constitution in aid of Indigenous recognition if the effect of the change will be to curtail its own legislative power ...

What is proposed is a voice to parliament, not a voice in parliament."

Professor Anne Twomey drafted the original proposed form of amendment.

"Her proposal demonstrated that a constitutionally entrenched Voice can be achieved without legal derogation from parliamentary supremacy."

[snip]

"Australians are unlikely to support constitutional change unless there is a substantial degree of Indigenous consensus in favour of the proposed change. Establishing and demonstrating that consensus, to parliament and to the general public, will itself provide a preview of the representative body that will follow."

[snip]

"A point that has been fairly made is that, if the proposed body is to have representative legitimacy, then its make-up will give rise to political issues and contest within the Indigenous community. Why that is a bad thing is not clear to me. Political action is the mechanism by which our own representative bodies are normally constituted, and through which they function."

[snip]

"Under the Constitution, the parliament may make special laws concerning the people of any race which, in practice, means Indigenous people. Does the Constitution treat Indigenous people in the same way as everyone else? Hardly.

" The race power, by its very existence, calls into question the assumption of equality ... How does it offend some principle of equality now to provide that, in recognition of the unique position of Indigenous people in the nation’s history, parliament shall establish a representative body that has a particular function of giving advice about such laws?

"It has been suggested that it is divisive to treat Indigenous people in a special way. The division between Indigenous people and others in this land was made in 1788. It was not made by the Indigenous people. The race power in the Constitution is now used in practice to make special laws for them. The object of the proposal is to provide a response to the consequences of that division."

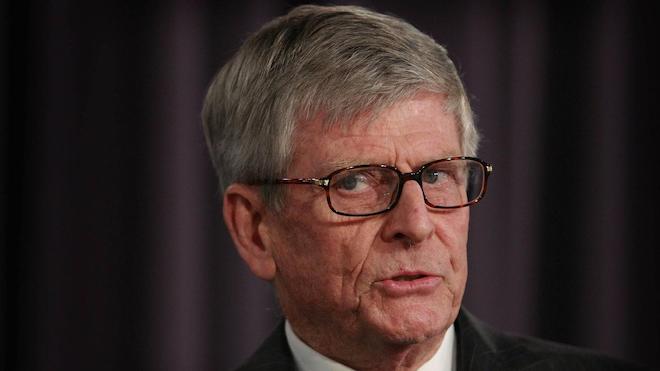

Ian Callinan

In The Australian (where else?) December 17, 2022

Ian Callinan: hopes for First Peoples welfare - but not the Voice

Ian Callinan: hopes for First Peoples welfare - but not the Voice

"Stretching my imagination only a little, I would foresee a decade or more of constitutional and administrative law litigation arising out of a voice whether constitutionally entrenched or not. Every state and territory is likely to have an interest in any representations and in the interactions between the voice and the constitutionally entrenched houses of parliament and executive government."

[snip]

"I have no doubt that, already, courageous and ingenious legal minds both are conceiving bases upon which to litigate the many legal and cultural implications of the voice. The voice, or a member of it, is almost certain to argue in the courts that a member of the executive government, in executing a parliamentary enactment of a representation of the voice, took into account an irrelevant consideration, or failed to take into account a relevant one, or made a decision that no reasonable person could make, shifting indicia relied upon in almost every challenge brought to the actions of government."

[snip]

"For the avoidance of any doubt, I restate my great respect and earnest hopes for the First Peoples’ welfare, improvement in life and full and undiscriminating involvement in Australian society in every respect. I write not only as an Australian, a former judge and a former patron of a charity for the support of troubled First Peoples’ youth, but also as a person who has had occasion to see in situ some sad circumstances of some First Peoples’ communities in or near Darwin, Ranger, Mornington Island, Thursday Island, Lockhart River, Alice Springs and Cherbourg.

"Like senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and many other Australians, including many, many lawyers of goodwill, I do not think the voice is the way."

Reader Comments